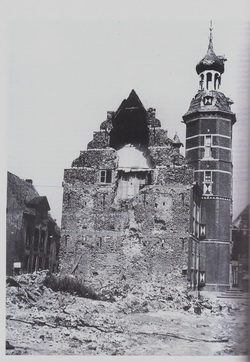

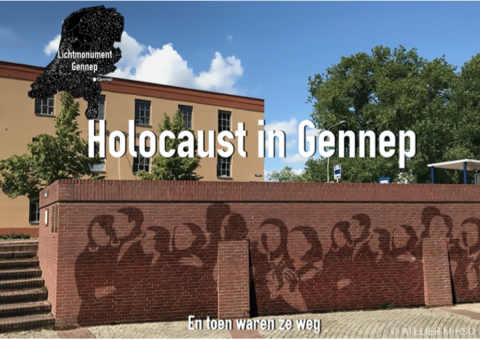

Genneps stadhuis HQ van de Black Watch |

|

U kunt het 75 jaar na dato allemaal meebeleven. De bevrijding van Gennep door de 51st British Highland Division. Ze hebben vandaag net als 75jr geleden hun hoofdkwartier opgeslagen in het Gennepse stadhuis. Na 2 dagen van hevige gevechten is Gennep veilig gesteld en kunnen de Highlanders verder optrekken richting Goch voor hun bijdrage aan operation Veritable. 460 duizend gealleerde manschappen rukken op richting het Rijnland en daarna door richting Berlijn.

Erg leuk voor de kinderen om dat eens te zien, met spullen van toen, met re-enactors.

En morgen volgt de officiele herdenking.

|

|

|

|

bij Nillessen is de pottenbakkersoven onder het zeil verdwenen en wacht op de toekomst.

|

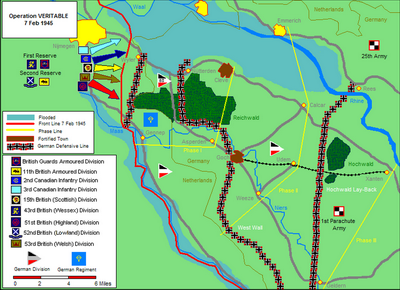

GENNEP en Operatie VERITABLE |

oe Gennep precies 75 jaar geleden bevrjd werd. Door Wie van Dinter

Debacle

In de strijd tegen Nazi-Duitsland op het Europese vasteland kwam de Engelse bevelhebber Montgomery in augustus 1944 in het oppercommando met zijn gewaagd strijdplan Operatie Market Garden . De opperbevelhebber van de geallieerde strijdkrachten Eisenhower was sceptisch: de aanvoerlijnen vanuit Frankrijk tot Brabant waren te lang; de opmarsstrook was erg smal; bij tegenslagen was er geen plan-B. Monty kreeg echter een aantal generaals mee en dus ging Ike met tegenzin akkoord. De uitslag van Market Garden(17-25 sept. 1944) is bekend: het offensief werd een debacle. In onze regio kwam het front stil te liggen aan de westkant van de Maas en bij Mook, Plasmolen en Groesbeek. Gennep bleef Duits.

‘Veritable'

Monty gaf niet op en kwam met een nieuw plan. Maar deze keer hield Ike voet bij stuk. Daar in Nederland geen nieuw offensief meer voordat de haven van Antwerpen in geallieerde handen was (korte aanvoerroute). Dat gebeurde pas eind november. Kort daarop (half december) lanceerden de Duitsers hun Ardennenoffensief , dat half januari doodbloedde. Toen kon Monty zijn nieuw offensief opzetten. Na ruim vier maanden na Market Garden kon het ECHT beginnen: Operatie Veritable .

Wedloop

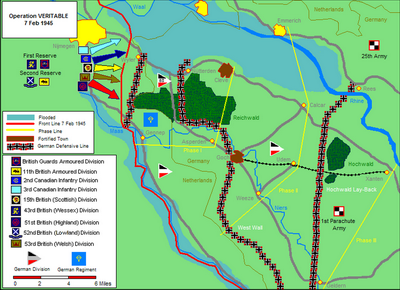

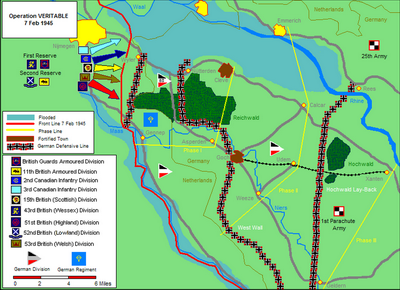

Operatiedoel was tweeledig: 1. Door het Reichswald naar Kleef en Wesel; 2. de Rijn oversteken en dan naar het Ruhrgebied en snel naar… Berlijn. Een wedloop met de Russen naar de Duitse hoofdstad. Want het Russische leger stond al voor Warschau. Aanvalsdatum: 8 februari 1945.

Snelheid is is geboden, de vijand moet overweldigd worden. De Luftwaffe speelt geen rol meer. De gevreesde Westwall eindigt in deze regio. Een snelle opmars moet mogelijk zijn. |

|

Het weer

Alle voorbereidingen werden gericht op donderdag 8 februari. Een formidabele troepenmacht werd bij Nijmegen samengebracht. Tussen Boxmeer en Beers stonden honderden vèrdragende kanonnen opgesteld. Alles onder controle behalve het weer. De tweede helft van januari vroor het overdag en 's nachts stevig. Begin februari sloeg het weer om: langdurende regen. De vorst trok uit de grond. Maas en Niers stroomden de uiterwaarden in. De oorlogsmachine was gestart. Weer of geen weer, alles was gericht op 8 februari.

De start

In de nacht van 7/8 februari worden Kleef, Goch, Uedem e.a. in het operatiegebied door honderden vliegtuigen met bommen bezaaid. Om 05.00 uur de 8 ste febr. breekt de hel los: meer dan duizend kanonnen spuwen een regen van gloeiend staal uit over het Reichswald om de Duitse defensie te verlammen. Precies 08.00 uur rijden vurende tanks met daarachter pelotons infanteristen bij Groesbeek over de vlakte naar de bosrand toe. De eerste tegenslag: de zware tanks rijden zich vast in de zachte, gedooide kleiachtige bodem en staan stil. De opmars moet verder en dus komen de voettroepen achter het beschermend staal uit en bereiken met zware verliezen de bosrand. Daar stapelen de tegenslagen zich op. De brandgangen en de verharde weg zijn bezaaid met granaattrechters en versperd door versplinterde, omgevallen bomen. Daarbij is het vijandelijk tegenvuur veel heftiger en zwaarder dan verwacht. Van progressie is nauwelijks sprake. De opmars stokt.

|

Gennep in beeld

Ontvangen rapportages doen het oppercommando al snel besluiten de aanvalsplannen te wijzigen. Besloten wordt het Reichswald te omsingelen en in te sluiten. Krijg controle over de wegen Grunewald-Kleef en Grunewald-Goch. Prioriteit krijgen Matterborn ten noorden en Gennep ten zuiden van het Reichswald . Dus rukken Canadezen vanuit Mook langs de N271 op en dalen de Britten de Plasmolense heuvels af richting Milsbeek, Ottersum en Gennep. De Duitsers hebben vier maanden de tijd gehad een hechte defensielinie op te bouwen. Voor de 4 km tot aan Gennep hebben de Schotten twee dagen nodig. De 10 de 's morgens bereiken ze de Kleineweg en hebben ze zicht op hun doel; de Niersbrug. De Duitse uitkijkpost in de Genneper Molen heeft hen waargenomen. Voor hun ogen blazen de Duitsers de brug op… |

Over de Niers

Overleg op hoger niveau: Gennep moet absoluut ingenomen worden en de brug hersteld, want er moeten tanks over die brug. Werk dus voor de Royal Engineers . Maar eerst moet Gennep in de nabijheid van de brug in Britse handen zijn. De Engelsen moeten dus Gennep in. Het plan wordt: in de nacht van 10/11 febr. In stormboten over de overstroomde uiterwaarden Gennep aan de noordkant naderen en post nemen in de verlaten Theresa-hoeve van Van Tol bij het Melkstraatje. In het holst van de nacht steken de stormboten in de Bloemenstraat van wal en verzamelen ze zich in de boerderij. |

|

Gennep in

In de ochtendschemering van de 11 de dringen de Schotten via de Haspel en de Maasstraat Gennep binnen. De gewaarschuwde Duitsers bieden felle tegenstand. Aan beide kanten ontstaan er gevechten van huis tot huis. Het duurt uren voordat de Britten uit de huizen in de Maasstraat, Doelen, op de Markt, Kerk-, Niers- en Houtstraat verjaagd hebben. Rond 11.00 uur kunnen ze hun kameraden aan de andere kant van de Nijmeegseweg het signaal veilig geven. De manschappen en Baileybrugdelen komen naar de Niers. De engineers beginnen aan hun haastklus. Een nog niet uitgeschakelde vijandelijke spandau m.g. beschiet voortdurend de bruggenbouwers. Ondanks doden en gewonden gaat de bouw onverdroten door; de brug moet ten koste van alles binnen enkele uren klaar. Geen wonder dat in de rapportages de brug de naam krijgt van Spandaubridge . Tegen de middag van 12 febr. rijdt de eerste brencarrier over de brug Gennep in.

Bevrijd

De verbeten tegenstand van de Duitsers kan nu makkelijker gebroken worden. De laatste grote opgave is de verovering van het station en het oversteken van de spoorlijn. Terwijl secties de buitenwijken van Gennep zuiveren, schakelt de hoofdmacht het verzet in de Logterheuvels en bij de molen uit. De Highlanders trekken nu over de N271 op naar Heijen. De commandant kan nu het hoofdkwartier melden dat Gennep na twee dagen felle strijd ingenomen is.

Vervolg

Heijen werd de 13 de na vinnige tegenstand -vooral bij de kerk en het Huis Heijen- van de Duitsers gezuiverd. Een gedeelte van de Britse troepen trekt richting Afferden. De andere pelotons gingen de Hommersumseweg op. De ergste tegenstand moesten zij bij de afslag Beltweg overwinnen. Daarna trokken zij tot bakker Beumler aan de Ned.- Duitse grens, waar hun strijdmakkers die via de Looi getrokken waren hen al opwachtten. Gezamenlijk drongen ze via Hommersum en Viller Mühle de 17 de op naar de weg Grunewald-Goch. De Duitse legereenheden in het Reichswald en bij Grunewald waren gewaarschuwd. Zij hadden zich ‘s nachts teruggetrokken op stellingen bij Goch. De eerste, bloedige fase in de Krieg am Niederrhein was ten einde.

Uitvoerig verslag van de bevrijding van Gennep in: W.S. van Dinter: Gemeente Gennep in de Wereldbrand. 1995. Pag. 153 e.v.

De heel mooi ingekleurde foto's zijn van Ton Wijers uit Afferden.

In the morning of February 8, 1945, Operation Veritable, also known as the battle of the Reichswald, was launched, led by Canadian General Harry Crerar. It was going to be the British and Canadian troops' largest operation since Normandy.

The aim was to destroy Nazi German positions between the River Maas and the River Rhine and to break through between these two rivers, allowing the formation of a front along the Rhine. The operation proved to be the turning point towards the end of the Second World War. It came at a high cost, however.

Almost half a million soldiers, more than 1000 guns and 34,000 vehicles lined the ten-kilometer-long front, ready for battle. They started their attack with heavy artillery fire, stunning their opponents. But to their dismay, the frosts had gone and the operation turned into an enormous mud bath. During the first days the soldiers struggled against landmines and mud.

|

|

In some areas, soldiers were left wading through freezing water up to their waists; the devastating explosions from hidden mines damaging tanks and vehicles, blocking the few usable paths; and as the rain continued to fall for days, the ground, churned up by shelling and heavy vehicles, turned into a thick porridge.

Surviving soldiers would go on to describe the Reichswald forest as a slaughterhouse, trees and buildings destroyed and recall brutal acts of violence and merciless close combat. Afterwards, Dwight Eisenhower described Operation Veritable as: "One of the fiercest and most violent campaigns of the war, a bitter struggle for endurance between the Allies and the Nazi Germans."

During Operation Veritable, the Allies lost 23.000 soldiers, including more than 5.000 Canadians – many of whom are buried or commemorated within the Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery and the Reichswald Forest War Cemetery just across the German border in Kleve.

The eventual success of Operation Veritable and the Rhineland Offensive paved the way for the continued liberation of Dutch cities and towns. With the Nazi Germans unable to defend the Rhineland area, the Allied commanders could confidently continue the liberation efforts in the rest of the Netherlands, and many of the surviving soldiers were sent north, west and south to help. |

Source: Remembering Operation Veritable - WWII, Blog post | 07-02-2020 | Netherlands embassy in Ottawa

The Battle Area

A S it made ready to launch its Rhineland offensive, the First Canadian Army, not for the first time, faced a difficult and disagreeable battlefield.

In the succession of directives and orders which were issued at all levels from army group down to battalion, the oft-repeated phrase "to destroy the enemy between the Maas and the Rhine" defined the battle area. At his final objective, the line Xanten-Geldern, General Crerar could contemplate a front of twenty miles between the two rivers. But 40 miles downstream, where the Army's present front line crossed them, Mook, on the Maas, was only six miles from Nijmegen, on the Waal. To reach their forward assembly areas in the restricted space about Nijmegen, all formations of the 30th Corps except the two Canadian divisions already in position had to cross the Maas, as well as the Maas-Waal Canal two miles west of Nijmegen. The movement would require a strict schedule of traffic control over the bridges at Mook, Grave and Ravenstein.

Within these natural boundaries General Crerar faced other limitations on manoeuvre. Although both river beds had been regulated into single, navigable channels, each was flanked by a wide flood plain in which backwaters, marsh and abandoned channels provided effective obstacles to movement. These flats were subject to inundation when excessive rainfall, such as had prevailed that winter, produced an unusually high water level in the rivers. Along the Maas, rising ground restricted the flooding to about 1000 yards on each side of the main stream; but in the Rhine and Waal flats the spread of the water was contained only by the winter dykes which stretched almost without interruption from the vicinity of Wesel down to Nijmegen, in general from one to three miles back from the river. Breaching these dykes would substantially increase the inundation; when this happened, as we shall see, the water in places encroached almost halfway to the Maas.

The greater part of the country between the rivers was open and gently undulating, largely arable, with a number of small woods. In general it was well suited

to armoured warfare. But just inside the German frontier the western end of this rolling plain was blocked by a large irregular forested area, some eight miles from west to east and four miles wide. This was the Reichswald. A dozen miles to the east the approach to Xanten was barred by the Hochwald and the Balberger Wald, which together formed a smaller belt of woods from one to three miles deep, extending six miles from north to south. The trees in these state forests were mostly young pines growing from four to seven feet apart. Each wooded area was divided into rectangular blocks by narrow rides, and there were occasional clearings where cutting had not been followed by replanting. Two paved roads crossed the Reichswald from north to south, converging on Hekkens, midway along the southern edge of the forest. None ran from west to east, so that military traffic in that direction would be dependent upon one-way tracks along the sandy rides, only some of which had been roughly metalled to make them passable for heavy timber trucks. Most of the Reichswald was level or gently rolling, but a curving ridge of high ground ran from Cleve through the northern and western portions, pivoting on the Branden Berg, a 300-foot hill in the north-west corner of the forest.

On either flank of the Reichswald topography again favoured a defending force. From the south-eastern angle of the forest the River Niers flowed westward across the rolling plain to enter the Maas below Gennep. Swollen by flooding and with its bridges blown, it formed a highly defensible obstacle. To the north a corridor of cultivated land about a mile wide ran between the edge of the woods and the Nijmegen-Cleve road (which marked the southern limit of the Waal flood plain). Towards Cleve this avenue narrowed considerably and was crossed by a number of low spurs which stepped up to the main Matterhorn ridge overlooking the city. Beyond Cleve the gap opened to give space to three roads which, diverging to the south-east and south through the widening plain, led to Calcar, Üdem* and Goch. Besides the Nijmegen-Cleve highway a second axis of advance was offered by the paved Mook-Goch road, which ran along the southern edge of the Reichswald, crossing the Niers at Kessel. At Gennep a road branched off to the south to follow the right bank of the Maas to Venlo.

The Enemy's Defences

The Germans had laid out their defences in a businesslike manner, exploiting the advantages of terrain favourable to themselves, and concentrating their strength here the country seemed most inviting to an attacker. They depended on three main fortified zones, each extending southward from their secure Rhine flank. The foremost ran across the western face of the Reichswald from Wyler on the Cleve road to the Kiekberg woods east of Mook, turning thence south-eastward to pass through Gennep and continue along the east bank of the Maas. In the first Canadian Army's sector this formidable outpost to the main Siegfried defences as based on a double series of trenches, covered in front of the Reichswald by

an anti-tank ditch. Villages and farmhouses had been converted into strongpoints, and connecting trenches from front to rear linked the whole into an elaborate defence system which extended in depth 2000 yards or more from the forward minefields to the rear field works along the edge of the forest. The strongest parts of the line were about Wyler and the Kiekberg woods, where the two main roads were defended in considerable depth with road-blocks, dug-in anti-tank guns and short stretches of anti-tank ditch. In the floodable area north of the Nijmegen-Cleve road the defences were relatively light. About three miles to the rear of these positions the northern end of the Siegfried Line constituted the second defence. The main belt crossed the Reichswald just east of the lateral road from Kranenburg to Hekkens. It then skirted the southern edge of the forest to Goch, where it turned south again to cover the approaches to Weeze, Kevelaer and Geldern. North of the Reichswald the corridor leading to Cleve was guarded by a succession of trench systems which reached back to positions on the high ground about Materborn. These were extended to the north by a system of field works which had been constructed across the flood plain from Donsbrrüggen to Duffelward on the Alter Rhein. In addition a line recently developed about two miles east of the forest linked Cleve with Bedburg and Goch and completed the circle of all-round defence about the Reichswald area.

Work on this end of the West Wall (the actual German name for what we called the Siegfried Line) had never been completed, so that instead of the formidable concrete to be found farther south there were only field fortifications--described by the German commander in that sector as "a haphazard series of earthen dugouts". The only concrete works were bunkers for sheltering personnel, and these were concentrated mainly in the Materborn area. The strongest parts of the line in the Canadian sector were to be found about Goch (which was protected on three sides by anti-tank ditches) and, as might be expected, in the defile north of the Reichswald. Here a concentration of fire positions which ran from the edge of the woods at Frasselt to the main Nijmegen-Cleve road was guarded by an anti-tank ditch which continued northward through Kranenburg and crossed the flood plain between Mehr and Niel to end at the Alter Rhein.

The enemy's third major barrier in the Canadian Army's path began at the Rhine* opposite Rees and ran southward in front of the Hochwald and Balberger Wald to Geldern and beyond. This "Hochwald Layback" consisted of two and sometimes three lines of entrenchments, from 600 to 1000 yards apart. Between these lines (except west of the Hochwald) ran an anti-tank ditch; and each trench system was further protected by a continuous belt of wire.

In recent months the Germans had attempted to bind these various defence positions into a single network in which a penetration at any point could be effectively sealed off. This aim had been best achieved in the Reichswald area, which had been split into a series of self-contained boxes enclosed by stretches of trench, ditch or river. Farther east, the emphasis had been on transforming the towns and

villages between the West Wall and the Hochwald Layback into individual islands of resistance, each encircled by elaborate trenchworks and anti-tank ditches.

At the beginning of February the Reichswald sector of the German front was held by Major-General Heinz Fiebig's 84th Infantry Division , which formed the right wing of the 86th Corps (under General of Infantry Erich Straube) and indeed of General Schlemm's First Parachute Army . Straube's left wing was the 180th Infantry Division which was deployed along the Maas. Across the Rhine was the 88th Corps , of the Twenty-Fifth Army , with the 2nd Parachute Division as Fiebig's immediate neighbour.

The 84th Division brought no brilliant record with it into the Reichswald defences. Formed in Poland early in 1944 from the remnants of worn-out infantry divisions and large replacement units, it had been virtually destroyed in the Falaise Pocket. It was reconstructed in September, and at the beginning of February its strength was 10,000, the majority green troops inadequately armed and equipped. This would have allowed Fiebig to man his forward line with seven battalions only, but on 6 February he was given the 2nd Parachute Regiment from the 2nd Parachute Division . This well-equipped formation of 2000 men recently drafted from the Luftwaffe he placed between the western tip of the Reichswald and the Maas. Next to them came the three regiments of the 84th Division : across the face of the forest the 1062nd Grenadier Regiment ; the 1051st Grenadier Regiment covering the corridor to the north, and the 1052nd guarding the Rhine flats on the extreme right. Fiebig held in the rear area the Sicherungs Battalion Münster (a small unit of elderly men normally employed on guarding static installations), and the 276th Magen (Stomach) Battalion , composed of personnel whose chronic digestive ailments ill fitted them for any active part in the defence. (Fiebig told interrogators that he had chosen the Magen Battalion in preference to an Ohren (Ear) Battalion , who were too deaf to hear "even the opening barrage of an attack".) The only German armour in the Reichswald area was some 36 selfpropelled assault guns of the 655th Heavy Anti-Tank Battalion . Fiebig's total artillery resources numbered about 100 guns.

Allied appreciations of these dispositions proved remarkably accurate. As to reserves available at short notice to the First Parachute Army , General Crerar's headquarters foresaw the possibility of the 7th Parachute Division being east of the Reichswald, and farther afield the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division , or its equivalent, which might be on hand within six hours of the assault. Actually part of the 7th Parachute Division was at Geldern, having been gradually edged that far north by General Schlemm, who claims to have vigorously opposed Army Group's view at the Allied attack would be made in the Venlo area. General Blaskowitz was holding his armoured reserve, the 47th Panzer Corps , at Dulken, a dozen miles south-east of Venlo. Its two divisions, the 116th Panzer and the 15th Panzer Grenadier , had been badly mauled in the Ardennes battle and according to the Corps Commander, General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, were at little better than 50 per cent strength and could jointly muster no more than 90 tanks. As possible reinforcements for the whole front facing the three northern Allied armies,

Field-Marshal Montgomery's intelligence staff estimated on 4 February that von Rundstedt might be able to assemble up to eleven Panzer and Panzer Grenadier divisions. Most of these, however, he would be forced to retain in the south to meet the American threat between Roermond and the Ardennes, or to send eastward to the Russian front.

The Pattern of "V ERITABLE "

As we have seen (above, ), the number and the expected strength of the enemy's lines of organized defences had led General Crerar to plan Operation "V ERITABLE " in distinct phases, with intervening pauses to allow him to regroup his assault forces and move forward his supporting artillery. His instructions to his Corps Commanders on 25 January confirmed that the operation would be carried out as originally outlined in his directive of 14 December. Naming the target date as 8 February, he laid down as a basis for planning the following principal phases and objectives:

"Phase 1 The clearing of the Reichswald and the securing of the line GennepAsperden-Cleve.

"Phase 2 The breaching of the enemy's second defensive system east and south-east of the Reichswald, the capture of the localities Weeze-Üdem-Calcar-Emmerieh and the securing of the communications between them.

"Phase 3 The 'break-through' of the Hochwald 'lay-back' defence lines and the advance to secure the general line Geldern-Xanten."

The initial assault and the completion of the first phase would be the responsibility of Lieut.-General Horrocks' 30th British Corps; thereafter, at a time to be settled by the Army Commander in consultation with Generals Horrocks and Simonds, the 2nd Canadian Corps would be committed on the left. Lieut.-General Sir John Crocker's 1st British Corps, strung out along the lower Maas, had, we have seen, the task of keeping the enemy deluded into expecting an offensive against northern Holland.

Horrocks was faced with the necessity of blasting his way through three strong German defence lines. "There was", he said later, "no room for manoeuvre and no scope for cleverness." With the low-lying area on his left flank flooded by the Germans, and the Mook-Goch road on his right completely dominated from the southern edge of the Reichswald, his only promising axis of advance lay north of the forest, along the road through Kranenburg. The key to a successful breakthrough was the Materborn Gap--the narrow neck of high ground between the Reichswald and the town of Cleve. Given favourable going over frozen ground, the Corps Commander hoped to break through this gap before it could be closed by German reserves and to flood the plain east of the Reichswald with troops before enemy reinforcements arrived. It might even be possible "with any luck . . . to seize the bridge over the Rhine at Wesel intact". As we shall see, however, the Wesel bridges were among the targets of the Allied air forces.

The Corps plan provided for the initial assault to be delivered on the sevenmile front between the Maas and the Waal by five infantry divisions--from right

to left the 51st (Highland), the 53rd (Welsh), the 15th (Scottish) and the 2nd and 3rd Canadian. The first four would attack simultaneously at 10:30 a.m. on D Day; the 3rd Canadian Division's operations on the northern flank would not start before evening. When the Scottish Division in the centre had secured the Materborn feature it was Horrocks' intention to bring forward the 43rd (Wessex) Division and the Guards Armoured Division from corps reserve and pass them through the gap to debouch into the open country south of Clevve-the 43rd directed on Goch and the Guards on Üdem.

The assaulting formations would be supported by unusually large artillery resources, for the Corps Commander was determined to blast a way into the German defences with gunfire. However, the guns, in the interest of surprise, would not fire until the morning of the attack. The fire plan was required to provide for an immense though brief artillery preparation programme which would prevent any enemy interference with the initial assault; complete saturation of the German defences and the destruction or neutralization of their concrete emplacements; then immediate supporting fire for the attacking infantry and armour, and the employment of the medium and heavy guns in such a way as to cover the deep penetration to the Materborn feature without involving the batteries in any major moves.

Weather permitting, "V ERITABLE " was to benefit by air support on the maximum scale. Planning for the air operations was carried out by Headquarters No. 84 Group R.A.F. in conjunction with Army and Corps Headquarters. Because of the unreliability of the weather and the impossibility of forecasting conditions more than twenty-four hours ahead, it was originally agreed that D Day might be postponed one day to allow for the provision of air support. On 1 February however, as we have seen, a decision of SHAEF that "V ERITABLE " would definitely commence on the 8th (above, ended the possibility of waiting for good flying weather.

The air forces assigned to the operation included heavy bombers of the R.A.F. Bomber Command and the United States Eighth Air Force, medium bombers of No. 2 Group of the 2nd Tactical Air Force, and fighter bombers of Nos. 83 and 84 Groups and the U.S. Ninth Air Force. To achieve the close coordination essential to the gigantic effort a representative authorized to make decisions on behalf of Bomber Command was attached to No. 84 Group during the planning and execution of the operation. Requests to SHAEF for the support of the Eighth Air Force were channelled through H.Q. 2nd Tactical Air Force.

The air plan provided for both pre-planned and impromptu air support. Before the "V ERITABLE " D Day railways, bridges and ferries leading to the battle area and elected enemy supply dumps would be bombed, care being taken not to indicate the actual point of attack. Heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force would attempt to put out of action the rail and road bridges across the Rhine at Wesel. On the Might of 7-8 February the towns of Cleve and Goch were to be completely destroyed by Bomber Command. Cratering in these cities was to be accepted as unavoidable; but this was not the case in a number of villages and small towns in forward as which were selected for attack by night intruders using incendiary and anti-personnel bombs.

On D Day itself the main air task was the destruction and demoralization of the enemy in the defences barring the northern corridor. The question of whether to accept cratering here posed a special problem. The military plan demanded that the bombing of these positions be followed by rapid exploitation by mechanized forces, but the R.A.F. warned that cratering was inevitable if a type of bomb was used sufficiently heavy to deal effectively with the concrete installations on the Materborn Ridge. Horrocks agreed to accept the possibility of shallow cratering on the Materborn feature, but not at Nutterden; there enemy troops in the open would be attacked with airburst bombs. In submitting the air plan to the 2nd Tactical Air Force the commander of No. 84 Group, Air Vice-Marshal E. C. Hudleston, stressed the significance of the Nutterden and Materborn targets. He defended the apparently uneconomical employment of medium and heavy bombers against these defences, pointing out that fighter-bombers were heavily committed on other tasks, and that "any effort which demoralizes the enemy and at the same time raises the spirits of our own assaulting troops" would not be wasted. As the battle developed it would be the task of No. 83 Group to deal with any counter-effort by the Luftwaffe and to isolate the battlefield by maintaining the programme of interdiction in the enemy's rear areas across the Rhine. No. 84 Group would operate over the battlefield itself, providing reconnaissance, close support, and "protection of ground forces", and striking pre-arranged targets--enemy headquarters, communications and ammunition reserves.

Great care was taken to ensure the 30th Corps effective impromptu air support once the battle had begun. Since No. 84 Group was operating with General Horrocks' Corps for the first time, machinery had to be set up for submitting targets and obtaining prompt and appropriate action. Staffs of ground formations were briefed in the procedure for submitting targets by the wireless and line communications of the 1st Canadian Air Support Signal Unit. At Corps Headquarters a Forward Control Post would operate a "cab rank" of fighter-bombers overhead, sending these in succession against accepted targets. It would be supplemented by a Mobile Radar Control Post, to be used for directing aircraft in bad weather. Because of the large number of formations that would be participating in Operation "V ERITABLE ", arrangements were made for contact cars to be deployed to headquarters of divisions. These mobile wireless links would serve as visual control posts and might be allotted aircraft by the Forward Control Post against specific targets, and in special circumstances given a small cab rank of their own.

Since "V ERITABLE " had to be a frontal attack, it was imperative that every effort be made to gain surprise. The cover plan, as we have seen, was calculated to keep the enemy's eyes on the 1st British Corps over in the west. To be effective it required the most careful concealment on the real battlefront. Here security measures had been stringently enforced during the vast administrative build-up (above, ). No daylight movement was permitted east of the 's-Hertogenbosch-Helmond Canal except for reconnaissance parties, and these, with formation patches removed from battledress, had to cross the Maas in Canadian vehicles accompanied by Canadian liaison officers. As the assaulting formations moved from their places of concentration to the forward assembly

area a Special Traffic Office employing 1600 men maintained rigid controls along all roads. To keep the roads clear for the arriving formations, no 2nd Canadian Division vehicle was allowed to move during darkness without the signature of a brigadier. An elaborate camouflage programme was devised to hide from hostile eyes the large concentration of artillery in the areas east and south of Nijmegen, and the huge quantities of stores, ammunition and petrol involved in the pre-battle dumping programme. Obviously dummy gun-positions were erected, the dummies being quietly replaced by real pieces as the build-up proceeded. A camouflage pool of specialist officers from Headquarters 21st Army Group directed the siting of ammunition in unrecognizable groupings which simulated hedgerows, kitchen garden plots and irregular patches of scrub. The Allied air forces were warned that the area about Arnhem and Nijmegen was closed to all aircraft up to 16,000 feet and that violations would draw intense anti-aircraft fire.

Such were the infinite pains taken to deceive the enemy. "Odd though it may seem", remarked General Horrocks afterwards, "we did achieve surprise."

First Canadian Army Goes Into Germany

The offensive opened early on 8 February. Luckily, the weather was favourable to air support. During the night the waiting troops had heard up to 769 heavies of Bomber Command roaring overhead on their missions of destruction against Cleve and Goch.* Then 95 Stirlings and Halifaxes from No. 38 Group R.A.F. unloaded more than 400 tons of bombs on Weeze, Üdem and Calcar. The flashes of the explosions and the fires which they started could be plainly seen by the soldiers in their assembly areas west of the Reichswald. At five in the morning the artillery preparation began.

As we have noted, the artillery support for Operation "V ERITABLE " had been planned as a major battle-winning factor. The concentration of fire which fell on the German 84th Division that day was probably not equalled on a similar front during the entire war in the west. It was calculated that 1034 guns--one-third of them mediums, heavies and superheavies--were engaged in the bombardment. Seven divisional artilleries, five Army Groups Royal Artillery, and two anti-aircraft brigades struck this massive blow, which was designed to harass the enemy's headquarters and communications, silence his batteries and mortars and smash his troop positions, destroying his forces and demoralizing survivors. In five bombardments during the day an average weight of more than nine tons of shells was to burst on each of 268 targets. The cannonade was augmented by four divisional "Pepper Pot" groups, which swept the front continuously with the coordinated fire, at relatively short range, of all available tank guns, anti-tank guns, light antiaircraft guns, medium machine-guns and heavy mortars. Rocket salvoes from the 12 projectors of the 1st Canadian Rocket Battery saturated thirteen targets in and about the German forward positions.

At 7:40 a.m., after a smoke-screen had been laid down across the whole front, there was a brief lull in the firing. As expected, these combined warnings lured the enemy into manning his guns and bringing down his defensive fire against an expected attack. The virtual silence that covered the battlefield for ten minutes enabled sound-rangers to locate one hostile battery and nineteen mortar areas. Then the bombardment thundered out anew, and it seemed as though every hostile position must be completely smothered. "It was good to see and hear", wrote The Calgary Highlanders' diarist, "especially to any of the old timers, as so many times we have gone in and would like more support than we got." The preparatory programme reached its climax as the barrage opened, and new notes were added by the sounds of armour grinding forward and aircraft roaring overhead. Afterwards dazed German prisoners told interrogators a grim story of disorganization--communications totally disrupted and gun-crews unable to man their guns until the barrage ceased. They said that the prolonged strain of the bombardment had created "an impression of overwhelming force opposed to them, which, in their isolated state, with no communications, it was useless to resist".

H Hour was 10:30 a.m. The covering barrage was to begin slowly on the opening line at 9:20, thickening up to its full intensity from 10 o'clock onwards. At H Hour it would begin to move. Smoke-shells mixed with the high explosive built up a protective white screen which blanketed the north-western edge of the Reichswald and effectively concealed the assault battalions of four divisions as they emerged from the woods behind Groesbeek and advanced down the forward slopes to their start-lines. If the enemy took this smoke as prelude to an attack, after his earlier experience he was reluctant to retaliate. As a deception measure the start lines across the front were being held by all the battalions of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division except the two taking part in the attack. At 10:29, as a line of yellow smoke-shells indicated the final minute before the barrage lifted, infantry and tanks began passing through the 2nd Division's positions to advance into Germany.* Except on the right flank (where the 51st Division was supported by prearranged concentrations on the estimated main enemy localities in that sector) the barrage, which was 500 yards in depth, advanced in blocks of 300 yards every twelve minutes. The same yellow smoke-signal one minute before the end of each block enabled the attacking troops to move with confidence immediately behind the curtain of fire and thereby reap the maximum advantage.

The guns had done their work so well, and so completely was the enemy surprised, that the initial attack met only light opposition. The stiffest resistance was on the right, where in the opening phase the 51st Highland Division (commanded by Major-General T. G. Rennie) had the mission of capturing the southwest corner of the Reichswald and opening the Mook-Goch road. The 154th Highland Brigade had varying success. On its left a Black Watch battalion had taken

its objective, the northern end of the Freuden Berg ridge, by two o'clock, but other troops were held up at Bruuk, 500 yards short of the frontier. The unexpected opposition came from a battalion of the 1222nd Grenadier Regiment (of the 180th Infantry Division ), hurriedly thrown in on the previous evening. The momentum of the advance was restored only when a battalion from the 153rd Brigade was passed through and drove forward into the forest. On the Division's right flank, the 153rd Brigade captured the Pyramide height and St. Jansberg at the edge of the Kiekberg woods. By four next morning, the whole of the Freuden Berg was secure, and Highland infantry had penetrated a further 200 yards south-eastward into the Reichswald.

In the adjacent 53rd Division sector the mud which was hampering the advance across the entire corps front bogged at the start-line the Flails detailed to clear the mines ahead of the assaulting tanks and infantry. But the commander of the 34th Armoured Brigade had already resolved to expend up to a squadron of tanks, if necessary, in getting the infantry to the edge of the Reichswald; and fortunately the extent of the minefields proved to have been greatly overestimated. Churchill tanks mastered the heavy going where others with narrower tracks had failed, and supported the 71st Brigade's attack across the open valley in the face of virtually no opposition. The armour found the antitank ditch narrow enough in places to negotiate unaided, and by two o'clock the 1st Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry had seized the commanding Branden Berg and the 71st Brigade was in control of the north-west angle of the forest. From this base the 160th Brigade sent two battalions forward through soaking rain which emphasized the unreality of the artificial moonlight. With meagre support--for of all the supporting arms only one tank squadron had survived the sodden tracks forward--the infantry steadily worked through the northern edge of the woods. There were few enemy checks. By shortly after midnight both battalions had crossed the Kranenburg-Hekkens road and were astride the Siegfried defences.

The 15th (Scottish) Division in the centre of the corps front was charged with breaching the Siegfried Line north of the Reichswald and capturing the high ground overlooking Cleve--the "Materborn feature". Assaulting side by side, each with one battalion up, the 46th and 227th Highland Brigades had trouble with mines; only one Flail reached the start line. Yet by keeping well up to the barrage, by 6:30 p.m. the infantry had taken their initial objectives--Kranenburg, on the Nijmegen-Cleve highway, and the Galgensteeg ridge, which projected from the north-west corner of the Reichswald and overlooked the main Siegfried defences. By this time the 46th Brigade's route forward from Groesbeek was all but impassable, for it had had to take the weight of both brigades when the 227th's axis farther north broke down completely early in the afternoon. Thus a special armoured breaching force from the 44th Lowland Brigade was delayed several hours, struggling in the darkness and rain with a miserable track jammed with traffic stranded along its entire length. The force was finally turned on to the main Nijmegen-Cleve road after a passage had been bulldozed through Kranenburg. The attack, which was to have started at 9:00 p.m., did not get under way until four next morning.

On the Scottish Division's left the 2nd Canadian Division had the tasks of capturing Den Heuvel and Wyler and opening the Nijmegen-Cleve road to just short of Kranenburg. With the bulk of his forces spread across the Corps front to screen the impending attack from the enemy, General Matthews gave this assignment to two battalions of the 5th Brigade. A small triangular area south of the highway about Wyler was regarded as the northern anchor of the enemy's front line, and its early seizure was essential to the rapid advance of the 15th Division beyond Kranenburg. In order to surprise and seal off the force defending Wyler, Brigadier Megill avoided the direct approach from the northwest, and instead ordered his left battalion to by-pass the town and cut the highway beyond, thence attacking Wyler from the rear.

So effective was the counter-battery and counter-mortar preparation on the 5th Brigade's front that there was virtually no reply from the enemy, and the two assaulting battalions formed up without a single casualty. Keeping well up to the barrage The Calgary Highlanders struck eastward through Vossendaal to the main highway, about half a mile beyond Wyler. Mines were the chief obstacle; the Highlanders suffered 24 casualties from Schü-mines , which the enemy had cunningly laid in visible rows on the ground interspersed with others hidden below the surface. "A" Company now advanced down the road and by midday had made contact with a battalion of the 15th Scottish Division on the outskirts of Kranenburg. On The Calgary Highlanders' right Le Régiment de Maisonneuve found that the bombardment had greatly simplified their task. They occupied with little difficulty the shattered remains of Den Heuvel (where an officer counted 46 enemy dead

in a small area, "without examining slit-trenches") and cleared to the apex of the brigade's triangle at Hochstrasse.

While sappers of the 7th Field Company R.C.E. began work on the highway west of Kranenburg, The Calgary Highlanders' "C" and "D" Companies turned back towards Wyler. The former, on the left of the road, ran into stiff fighting in which the company commander and a platoon commander were killed. To keep the operation moving the Commanding Officer committed "B" Company, and after supporting fire had been called down on the objective, "B" and "D" pressed on into Wyler, reporting it clear by 6:30 p.m. Early plans had called for the roads forward to be open for traffic by four o'clock, but with the delay in taking Wyler it was nine before the sappers could report all routes free of mines. The operation had cost the battalion 67 casualties, including 15 killed. The Maison neuves lost two killed and 20 wounded. The brigade had taken 322 prisoners, most of them having been trapped in Wyler.

On the 30th Corps' watery northern flank the 3rd Canadian Division's part in "V ERITABLE " did not begin until 6:00 p.m. General Spry's task was to secure the left flank of the 2nd Canadian and 15th Scottish Divisions and clear the area between the Nijmegen-Cleve road and the river. This would be done by the 7th Brigade on the right and the 8th on the left as far as the anti-tank ditch from Donsb&ruml;uggen to Duffelward, at the edge of the main Siegfried Line. The 9th Brigade was then to break through these defences and advance east to the Spoy Canal, which led from Cleve to the Alter Rhein.

The effects of the sudden thaw and the heavy rains were more apparent on the 3rd Division's low-lying sector, the Waal Flats, than anywhere else on the whole Corps front. Drainage ditches that would normally have carried off the excess water were too badly damaged by gunfire to function effectively. The Waal had been rising steadily since 3 February. Records covering 34 years showed that only six times in that period had the February peak level at Nijmegen exceeded twelve metres.* Yet on D plus 1 of "V ERITABLE " the river was to pass this height, and to continue to rise to a top of 12.69 metres on 17 February. Earlier in the winter the Germans had breached the main dyke at Erlekom, four miles east of Nijmegen, and on the 6th water began pouring through this gap. Two days later the milelong Quer Damm just inside the German frontier, weakened by the enemy's digging of defence positions, collapsed before the pressure of the rising floods. Through the break water began pouring eastward towards the villages of Zyfflich and Niel. By D Day most of the 3rd Division's area of operations was submerged. On 3 February "soft-going" plans had been substituted for those previously made. This meant principally that the infantry would ride to their objectives in amphibious vehicles (the 79th Armoured Division provided 114 Buffaloes), and would be largely deprived of armoured support.

Only in the initial stages of the 7th Brigade's attack could the advance be made on dry ground. The Regina Rifle Regiment, attacking under artificial moonlight,

and supported by tanks of the 13th/18th Royal Hussars (Queen Mary's Own), seized the south end of the Quer Damm, and by eight o'clock had cleared Zyfflich, a mile to the east, digging about 100 prisoners out of its cellars. "B" Company of the Canadian Scottish, after two unsuccessful attempts to capture a strongpoint at the north end of the Quer Damm, finally took it at first light on the 9th. The battalion's remaining rifle companies, embarking in Buffaloes from the Wyler Meer, set course by compass through the darkness for Niel, two miles east of Zyfflich. Communications failed, and shortly after midnight the C.O., Lt.-Col. D. G. Crofton, headed towards the objective with his command group in two amphibians. But Niel was still in German hands, for the Scottish "A" and "D" Companies through faulty navigation had become engaged with a group of houses 1500 yards to the south-west. Crofton's party ran into point-blank fire from houses on the western outskirts. Two officers and two men were killed, and the C.O. and his Intelligence Officer were among the wounded. Day was breaking when "A" and "D" Companies arrived to clear the village.

On the division's left flank two Buffalo-borne companies of the North Shore Regiment, leading the 8th Brigade's attack, quickly secured the main dyke west of Zandpol and by 9:00 p.m. had reported the village itself free of enemy. Farther south Le Régiment de la Chaudière, forced at times to wade through three feet of water, occupied Leuth early on the 9th, opening the way for the brigade's next phase of operations.

"V ERITABLE " had made a good beginning. On the first day of the battle the 30th Corps had broken through the enemy's strong outpost screen and closed to the main Siegfried defences. It had inflicted severe losses upon the ill-fated 84th Infantry Division . Taking more than 1200 prisoners and killing a good many men besides, it had virtually destroyed six German battalions. There was encouraging news from prisoners who had helped to dig trenches in the Reichswald that the main defence line contained no concrete works. The problem now was how to exploit our gains before enemy reinforcements arrived in strength. The rapid deterioration of the maintenance routes forward was seriously impeding deployment of General Horrocks' formations. Particularly disturbing was the flood situation; between 1:00 p.m. and midnight of the 8th the water level north of the Nijmegen-Cleve road had risen eighteen inches.

The Siegfried Line is Breached

On 9 February low-hanging clouds and heavy rain which persisted well into the afternoon put a stop to our hitherto excellent air support* and indicated still worse going across the waterlogged fields and along the churned-up tracks of the Reichswald. The 2nd Canadian Division, having completed its limited task, had been pinched out of the battle, leaving four divisions to continue the advance during the next 24 hours.

Pursuing its sweeping manoeuvres over the flooded Waal Flats, the 3rd Canadian Division, whose sector now covered more than half the Corps front, took its village objectives one by one. In the 8th Brigade's advance next to the river the North Shore Regiment found that enemy resistance lessened as the flood waters deepened. The New Brunswickers met little opposition in capturing Kekerdom, and from there Brigadier Roberts sent the previously uncommitted Queen's Own Rifles of Canada forward to establish themselves without difficulty in Millingen.

The capture of Niel had given The Royal Winnipeg Rifles a base from which to extend the 7th Brigade's operations eastward. During the afternoon "A" and "B" Companies occupied Keeken and "C" pushed on to the Customs House on the Alter Rhein, an operation which the Brigade diary termed "quite sticky with a good bag of PWs". In Brigadier Spragge's right sector the Regina Rifles found Mehr free of enemy troops. Its capture ended the 7th and 8th Brigade's tasks. Indeed, the rising water virtually cut off the battalions on their objectives, where they had to exist as best they might until Buffaloes became available to evacuate them. It remained for the 9th Brigade to complete the 3rd Division's role in the first phase of "V ERITABLE ".

But while the northern tip of the Siegfried Line had still to be overcome, before the second day of the battle ended the main defences had been penetrated by two of the divisions attacking south of the Nijmegen-Cleve road, and on the Corps' right flank the Highland Division's 153rd Brigade had cut the important Goch road at two points between Mook and Gennep. Units of the 6th Canadian Brigade could see the 1st Gordon Highlanders working southward across their front clearing out the area between the Kiekberg woods and the Maas, and on several occasions were able to assist with information about enemy movements. Meanwhile the 152nd Brigade, passing through the 154th, had fought forward through the southern half of the Reichswald as far as the Kranenburg-Hekkens road, just short of the main entrenchments. Farther north the 53rd Division had measured off substantial gains. Attacking at 8:30 a.m. from the positions gained during the night, two Welsh battalions of the 160th Brigade, supported by the 9th Royal Tanks, pushed two miles eastward to the Stoppel-Berg, a circular mound 300 feet above sea-level and the highest point in the Reichswald. The 2nd Battalion The Monmouthshire Regiment* captured the hill after sharp fighting. The stiffening enemy resistance was evidence of the arrival of strong reinforcements, as were the determined counter-attacks launched against the East Lancashires holding the Kranenburg equines road. These were beaten off with the aid of eight tanks of the 147th Regiment Royal Armoured Corps which had mastered the almost impossible roads forward. Before the day ended the 6th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, exploit beyond the Stoppel-Berg, had reached the north-eastern edge of the Reichswald overlooking Materborn, whence supporting tanks found attractive targets in traffic on the Cleve-Hekkens road, now the enemy's main lateral communication through the forest.

But it was in the corridor between the northern edge of the Reichswald and

the flooded Canadian sector that the most spectacular progress had been made. The 15th (Scottish) Division's original plan to advance by leapfrogging its brigades and battalions in successive phases was frustrated by the appalling conditions of mud and traffic congestion on the routes forward. Day had broken by the time the 44th Brigade's Special Breaching Force had bridged the anti-tank ditch at three of five planned crossing places east of Frasselt. At 6:15 the 6th Battalion The King's Own Scottish Borderers, borne in Kangaroos of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, began to cross. (Their eight-hour journey forward from Nijmegen was afterwards described by the K.O.S.B. battalion commander as "a remarkable display of skill and endurance by the drivers of the APCs".) By eight o'clock the K.O.S.B. had cleared Schottheide, 500 yards to the east; shortly afterwards the 2nd Battalion The Gordon Highlanders, advancing along the main road from Kranenburg, were on the outskirts of Nutterden. There was no sign of the battalion which had been detailed to exploit these gains. Accordingly, the Borderers went forward again in Kangaroos to capture the Wolfs-Berg and the HingstBerg--a pair of knolls between Nutterden and the forest. These were taken about midmorning with the assistance of a squadron of Grenadier Guards tanks; and the clearing of Nutterden by the Gordons completed the second phase of the Division's attack. The operation was now eleven hours behind schedule and it was imperative to carry out the final phase--the capture of the Materborn heights overlooking Cleve--before the Germans further reinforced these key positions. Since there was no hope of bringing the 46th and 227th Brigades forward in time as planned, the G.O.C., Major-General C. M. Barber, was compelled to order the Lowland Brigade to push on still further. The 8th Battalion Royal Scots seized the Esperance hill, the nearer of the brigade objectives, with little difficulty. The K.O.S.B., climbing once more into their Kangaroos, headed along the muddy tracks for the Bresserberg feature, less than half a mile from the city. They reached their goal with a scant half-hour to spare; at 5:00 p.m. they had to fight off elements of the 7th Parachute Division moving up to occupy the position. In the evening the 15th Division's reconnaissance regiment reported that the Germans in Cleve seemed disorganized and unlikely to offer resistance. But south of Cleve its patrols seeking a route eastward found their way blocked by a coordinated defence in Materborn village.

Through the Materborn Gap

The 30th Corps had done well in taking virtually all its objectives for Phase One of "V ERITABLE " in the first two days. The vaunted strength of the West Wall was found to have been much exaggerated, but this was discounted by the atrocious conditions of mud and flood with which the attackers had to contend. Yet they had struck the enemy a telling blow. It was estimated that the 84th Division had at best only six battalions left out of fourteen. By the second night the count of German prisoners stood at more than 2700. The tasks for Phase Two were to capture Goch, Üdem and Calcar and open

he Mook-Gennep-Goch road. It was imperative that Goch and Cleve should be secured with the least possible delay, for both were vital to our communications, as the enemy must recognize. On the 9th our Intelligence forecast his intentions thus: Cleve being "all but lost", "If he has forces available either from the Hochwald or from across the Rhine, he will be tempted to try to regain Cleve or at least seal it off. If he cannot do so then he must hold Goch, and also cover the nearest crossings of the Rhine."

It was an accurate appreciation. As late as 12:30 p.m. on 10 February General Blaskowitz received from the C.-in-C. West a signal emphasizing the incalculable consequences of a break-through to the Rhine and the necessity of holding Cleve at all costs. For the first time the German High Command now appears to have recognized the First Canadian Army's offensive as a strategic move demanding the commitment of all available reserves of men and equipment. Our security measures had been effective. Von Rundstedt's Daily Intelligence Reports reveal that up to now the main Allied attack had been expected at the bend of the Maas north of Roermond,* where the Second British and Ninth U.S. Armies were believed to be preparing a strong two-pronged offensive against the Duisburg-Dusseldorf sector. Three days before "V ERITABLE " was launched a memorandum from Rundstedt's Chief Intelligence Officer to key staff officers at Headquarters Army Group "H" (who had perhaps questioned this interpretation) suggested that Allied activities west of the Reichswald were intended "to deceive us regarding the real centre of gravity of the attack". A subsidiary offensive by Canadian formations in the Reichswald area might precede the main effort. With impressive assurance the memorandum concluded, "The appreciation that the main British attack will come from the big bend of the Maas is being maintained now as before." In the German intelligence picture the 30th British Corps was labelled "whereabouts unknown".

The opening of the offensive on 8 February brought no change of mind. It was thought that evening that the attack had probably been carried out by the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions, supported by the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. The main blow was still expected to fall south of Venlo. Even when the 51st and 53rd Divisions were identified in the Reichswald on the 9th, German Intelligence clung to the belief that the bulk of the British forces was earmarked for the main assault from the Maas bend. The enemy had already taken steps to delay the start of this operation, steps which in fact were to hamper us severely. On 9 February units of the First U.S. Army, having captured some of the Roer dams intact, reached the important Schwammenauel Dam to find that the Germans had jammed open a sluice gate.† There followed a rise of from three to four feet in the level of the Roer, which caused the river to overflow its banks across the

whole of the Ninth U.S. Army's front and produced a lesser rise along the Maas in the First Canadian Army sector.

The timing and scale of this action could not have been better from the enemy's point of view. Complete demolition of the dam would have released an uncontrollable, but brief-enduring, tide to sweep down the Roer valley. As it was, the flood level, which was high enough to stop the Ninth Army's assault, was to maintain itself for two weeks. Operation "G RENADE ", originally scheduled for 10 February, had to be repeatedly postponed, and von Rundstedt was free for the time being to concentrate upon the operations developing on his north-eastern flank. On the evening of the 8th Army Group had given Schlemm permission to commit the 7th Parachute Division . Arriving piecemeal by battalions it had taken up positions on the left of the 84th Division between Asperden and the Maas. Late on the 10th von Rundstedt decided to move up his armoured reserve and to place Headquarters 47th Panzer Corps in control of the battle.

On our side divisional tasks for the third day of "V ERITABLE " were as follows. While the 51st Division continued to mop up east of the Maas, and to free the southern route to Goch, in the north the 43rd Wessex Division would be brought forward to pass through the 15th Division and capture Goch, Üdem and Weeze. The Scottish Division would then clear Cleve and push mobile columns eastward to Emmerich and Calcar.

For the next forty-eight hours the focal point of the battle was to lie in the narrow Materborn Gap between the Reichswald and the heavily bombed city of Cleve. The 30th Corps plan had contemplated a quick breakout into the plain east of the forest by the 43rd Division. To this end Phase One of the Corps operation had included with the "capture of the Materborn feature" the opening of exits through which the 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment* might pass. As we have seen, however, the 15th Scottish Reconnaissance Regiment had made little headway with this assignment. The Materborn Gap, in spite of the 44th Lowland Brigade's notable advance, was by no means under control. Yet the need of debouching quickly into the open country while the enemy was off balance was so pressing that when General Horrocks heard that the Materborn feature had been seized he at once ordered the 43rd Division into the battle. "In point of fact", he said afterwards, "this was a mistake on my part because 15 (S) Div had only just got their claws on to the Materborn feature and had not succeeded in dominating the complete gap. . . . It would have been much better if I had held back 43 (W) Div, but I did not want to lose the opportunity of breaking through the gap."

Since the afternoon of the 8th the Wessex Division had been waiting in the southern outskirts of Nijmegen on one hour's notice to move, and at 6:00 p.m. on the 9th its 129th Brigade took the road to Kranenburg and Cleve. General Thomas' plan was to advance eastward from Nutterden through the neck of the Reichswald, bypassing Cleve and pushing forward to Hau and Bedburg in order

to secure the fork of the roads to Goch and Üdem. The 214th Brigade followed the 129th, with instructions to pull off the main road at Nutterden between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m. on the 10th, to enable the 15th Division's 227th Brigade to move up and carry out its original task of securing the wooded area north-west of Cleve and clearing the city itself. But events were to emphasize the impossibility of successfully operating two divisions on a single axis--particularly an axis which in places was under water. About daybreak the 129th Brigade, leaving the impassable Bresserberg route, swung north to the south-west edge of Cleve, where it became heavily involved with the 1 6th Parachute Regiment , newly arrived from the 6th Parachute Division 's area west of Arnhem. Under pressure from three sides the brigade adopted a posture of all-round defence and fought on through the whole day and the following night.

Meanwhile the inevitable traffic jam had occurred when the 227th Brigade attempted to pass through the 214th at Nutterden. The congestion lasted till dusk, so that once again the 44th Lowland Brigade was the Scottish Division's only formation in action that day. By capturing the prominent Clever Berg the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers extended the brigade's hold on the Materborn feature northward to the road from Nutterden; but a planned advance into Cleve was abandoned when the 129th Brigade's unexpected presence on part of the objective prevented the 15th Division's artillery from giving the necessary support.

At the end of a frustrating day there was promise of confusion giving place to order on the morrow. Relieving the 129th Brigade, the Scottish Division would clear Cleve with two brigades, while the 43rd Division resumed its delayed advance to the south-east. Early on 11 February the Lowland Brigade took over the southern suburbs of Cleve from the 129th and began working northward through the rubble of the town, encountering determined opposition. By late evening the 227th Brigade had come in on the road from Kranenburg and was clearing the north-eastern half of Cleve. The capture of Materborn village that afternoon by the 214th Brigade had finally opened the gap. Fighting forward against sternly resisting paratroopers, this brigade took Hau by daybreak on the 12th.

Here however the advance was checked. To bar the way to the south the .enemy had established a defensive line along the Esels-Berg ridge which linked the woods about Moyland with the detached Forest of Cleve, east of the Reichswald. This was less than he had hoped to do. As the 47th Panzer Corps moved westward during the night of 11-12 February to its assembly area at Üdem, its commander, General von Lüttwitz, carried orders from General Schlemm to launch a counter-attack through the 84th Division to recover Cleve and the heights west of the city. But by the morning of the 12th, when the attack was to have been launched, British forces had advanced south-east from Cleve as far as Hau and in the eastern Reichswald were threatening the Cleve-Goch road. In these circumtances, and because of his shortage of tanks (not more than 50 actually on the ground) von Lüttwitz decided to attack westward into the Reichswald, where the Allied superiority in armour and artillery would be less effective. The assault would be made with the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division on the left and the

116th Panzer Division on the right. Von Lüttwitz planned that after reaching the Cleve-Hekkens road he would concentrate all his forces in a drive northward towards the Materborn heights.

The effort had failed. Scheduled to begin at 6:00 a.m., the German attack did not get under way until half-past nine. By that time units of the 43rd Wessex Division were pushing south-eastward towards Bedburg and southward along the Goch road. The German blows could not halt the momentum of the British drive. The Wessex Division's historian reports three counter-attacks launched against the 7th Somerset Light Infantry, "only to wither away in the fire of the infantry, the tanks and the guns". By evening the 47th Panzer Corps counter-attack had collapsed. Both its divisions had suffered heavily, and of the 84th Infantry Division only the 1052nd Grenadier Regiment could now muster any appreciable strength. Striving to put together a defensive line which would halt us, von Lüttwitz hurried in from across the Rhine a regiment of the 346th Infantry Division , committing it east of Bedburg under Fiebig. An operation order of the 116th Panzer Division dated 13 February reveals that this division now had the remnant of the 84th under command; and that it was to "break off the attack south of Cleve" and take up a defensive line running from Erfgen through Hasselt to the west edge of the Tannenbusch (the Forest of Cleve). The assault on this new position by the 129th Brigade on 13 February was the beginning of a bitter five days' struggle by the Wessex Division to gain control of the relatively high ground overlooking Goch from the north-east.

While progress in the centre of the 30th Corps front was thus bitterly contested, things had been going better on the wings. The most significant advance was on the right, where the 51st Division was endeavouring to open up the Mook-Goch road, now to be the main Corps axis. On 10 February the 153rd Highland Brigade, clearing the widening triangle between the Reichswald and the Maas, entered Ottersum, and during the night sent the 5th Black Watch across the Niers River in assault boats to capture Gennep. The town was a valuable acquisition, for the Second British Army was now able to begin bridging the Maas here* in order to relieve the traffic bottleneck downstream at Grave. On the 11th Hekkens, the troublesome southern anchor of the main Reichswald defences, was taken in fierce fighting by the 154th Brigade, supported by the full Corps artillery. Two nights later the same brigade, crossing the swollen Niers south of Hekkens in Buffaloes, established a bridgehead west of Kessel, capturing high ground from which the enemy had been directing fire upon the new Corps axis. On the night of the 14th-15th Kessel was taken. In the Reichswald itself the 53rd Division continued mopping up pockets of resistance. The worst opposition came from German self-propelled guns firing down the open rides, for there was no way of approaching these with armour. On the 12th the Welshmen successfully fought off the vigorous counter-attacks launched against them by the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division as the main blow of the 47th Panzer Corps' mistimed effort.

uit: The Battle of the Rhineland

Part I: Operation "V ERITABLE "

8-21 February 1945, ministerie van defensie, Canada

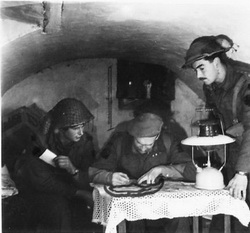

Illegalen in Gennep, eind 1944: deel 3 |

Het gehele verhaal kunt u ook nalezen op de special "Illegalen in Gennep, eind 1944".

November

De kruik gaat net zo lang te water tot ze breekt. Dit spreekwoord werd helaas van toepassing op de illegale kelderbewoners. Wekenlang vonden ze hun toevlucht in de voorraadkelder in de heuvelwand. De mannen hadden direct voor de ingang een dijkwand van zand opgeworpen zodat eventuele granaatscherven in de dijk smoorden. De hoge moutfabriek hield de koude noord- en oostenwind grotendeels tegen,; de massieve zanddijk voor de ingang deed de rest. Dik aangekleed was het in de kille novemberweken binnen goed uit te houden. Voor de in de buurt gelegerde militairen hoorden zij bij de burgers in de fabriekskelders. De verstandhouding met Duitsers was gemoedelijk. Er waren enkele soldaten bij uit de naburige Duitse grensstreek. Een van hen kwam wel eens kijken naar de jongste kelderbewoner, die nog in de kinderwagen lag.

Bezoek

Tijdens de laatste week van november kwam een hoge Duitse Oberst-Artzt met zijn gevolg in een Rode Kruiswagen de twee sanatoria in Gennep bezoeken. Hij sprak met de woordvoerders van de instellingen, nam de precaire situatie ter plaatse in ogenschouw en gaf aan, dat onmiddellijke evacuatie geboden was. Daarna reed hij naar de moutfabriek voor een afsluitend gesprek met de daar verblijvende doktoren Bauer, Daan en Muller. Geagiteerd door de in Gennep aangetroffen crisistoestand verliet hij de fabriekskelders.

Betrapt

Toen hij in de auto wilde stappen zag hij in het schemerdonker twee mannen lopen. Het was spertijd (avondklok 20.00 uur). Hij sommeerde zijn adjudant de mannen aan te houden en bij hem te brengen. Uit het volgend gesprek bleek dat de mannen tot de illegale bewoners uit de dijkkelder behoorden. De Oberst reageerde ziedend, ook nog illegalen! Hij blafte de Gennepse Ortskommandant in zijn gevolg toe te controleren of de illegale groep om 21.00 uur vertrokken was. Donker of niet donker, onmiddellijk Gennep uit! Hij verwachtte morgen een bericht, dat ze uit Gennep vertrokken waren. |

|

|

|

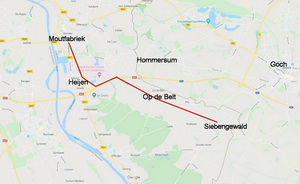

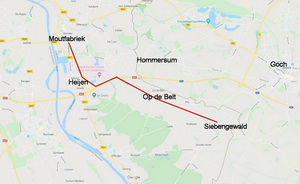

Op weg

De 21 illegalen (vier gezinnen, waaronder 3 kleine kinderen en 2 onderduikers) moeten hals over kop 's avonds om 21.00 uur weg uit hun kelder. Twee slaperige kinderen aan moeders hand, het derde kindje in de kinderwagen. De donkere koude nacht in. Waarheen? Gennep is afgesloten, dus de andere kant op richting Heijen. Naar Afferden? Te gevaarlijk zo dicht langs de Maas. In Heijen dus maar de Hommersumseweg op. Hoe ver dan in de nacht? Ze besluiten op de Kamp bij een boer te vragen daar de nacht te mogen doorbrengen. Koud en verkleumd krijgen ze bij boer L. die nacht onderdak. Ze mogen zich warmen, krijgen warme melk en moutkoffie. En de boerin maakt voor de allerkleinste een flesje aangelengde melk klaar. |

Beraad

De boer en de mannen overleggen waar de groep morgen heen zal trekken. Na enig beraad wordt men het eens: niet via Hommersum Duitsland in, maar over de Belt naar Siebengewald. De mensen daar zijn nog niet geëvacueerd. Wellicht kunnen ze daar blijven. Zijn ze gelukkig nog in Nederland.

De volgende morgen krijgen de Gennepenaren gebakken aardappelen met spek van de boerin. Daarna gaat men op pad, de grote jongens de kinderwagen duwend. Zon en wolken wisselen elkaar af; het is god zij dank droog. Na een poosje lopen slaan ze af naar de Belt. Het is een verlaten zandweg, die wel eindeloos lijkt met hier en daar in de verte een boerenhoeve. De weg is bedoeld voor grote karwielen; de kleine kinderwagenwieltjes rijden telkens vast in het losse zand.

De Belt

De twee kleintjes klagen dat ze moe worden en mogen bij de mannen afwisselend op de schouders zitten. De drie tieners sleuren de kinderwagen mee. De moeder loopt ernaast om de zaak in de gaten te houden. Bij het huis op de Belt krijgen ze water en melk. En dan gaat de tocht verder. Eindelijk zien ze links in de verte de kerktoren van Siebengewald. Daar zullen ze proberen onderdak te krijgen. En dat lukt. De groep van 21 kan in de grote hooischuur van boer B. terecht en valt de dagen daarna uiteen op verschillende adressen in het dorp.

Legaal

Zo kwam de groep uit Gennep verjaagden eind november in het grensdorpje aan. Ze bleven daar tot begin januari 1945 en moesten toen met Siebengewald evacueren. Door Duitsland kwam men in Oost- en Noord-Nederland terecht. De laatsten vonden in het terpdorpje Hallum boven Leeuwarden hun eindbestemming. Daar werden de ‘zigeuners uit Limburg' gastvrij ontvangen. Ze leefden en werkten er bij de Friezen zonder oorlogsgeweld tot de capitulatie in mei 1945. In juli 1945 keerden zij in een uitgewoond, door Britse militairen bezet Gennep terug. Met een town-major als baas. Maar goddank weer legaal thuis. |

|

Ansichtkaart van Siebengewald van voor WOII met nog de oude kerk, die op 24 februari 1945 door de geallieerden werd plat gebombardeerd. |

Wiel van Dinter, 7 feb 2020 |

grensovergang Siebengewald |

Illegalen in Gennep: Deel 2 |

Burgers in Gennep

Na 16 oktober 1944 was met medeweten van de Duitsers alleen de burgerbevolking behorend bij de twee sanatoria nog aanwezig in Gennep. De wachtposten op de in-/uitvalswegen (Niersbrug, Picardie en Spoorwegovergang) controleerden de passanten. Bij ‘Maria Oord' verbleven de burgers in de omliggende huizen en in het zusterklooster. ‘Zonlichtheide' kon weinig burgers herbergen. Die betrokken lege woningen aan de Heijenseweg en de twee kelders in de moutfabriek ‘Aurora'.

Heuvelkelder

De vier gezinnen, die besloten hadden het bevel tot evacuatie te negeren, hadden een goede schuilplaats op het oog. Links in de Moutstraat lag een half verscholen kelder. Deze was al vóór de oorlog door de eigenaar van de Moutfabriek Fr. Beckers in de heuvelhelling uitgegraven en gemetseld. Deze grote ruimte werd door de familie gebruikt als voorraadkelder met aardappelen, fruit e.d. Een ideale verblijfruimte in deze oorlogsomstandigheden. Met bossen stro en uit verlaten woningen ‘georganiseerd' beddengoed waren er slaapplaatsen te creëren. Voor de Duitse soldaten van de artilleriestelling verderop waren zij ook bewoners van de fabriekskelders.

Loopplan

Deze burgergezinnen, vanaf nu illegaal in Gennep aanwezig, hadden nog één probleem op te lossen. Hoe namen ze de etensvoorraad (varkens, geiten) mee naar de kelder? Ze moesten de wachtpost bij de spoorwegovergang vermijden. Ze besloten ‘s nachts met zijn allen inclusief het vee het spoor halverwege de Maasbrug over te steken en dan in de Moutstraat uit te komen. Het vee zouden ze daar weer terugzetten in de stallen achter de verlaten huizen van de Heijenseweg.

de spoorwegovergang met de wachtpost van de Duitsers.

de spoorwegovergang met de wachtpost van de Duitsers.

De oversteek

In de nacht van 16 op 17 oktober ging de groep van 21 door de achteruitgang van het patersklooster de grote tuin in. Varkens en geiten uit de stal aan een touw, het kleinste kind in de kinderwagen. Op weg naar de ‘heuvelkelder'. Om de wachtpost bij de overweg te ontwijken liepen ze behoedzaam en fluisterend tussen de verlaten huizen van het Voorhoevepark door naar het Spoorwegje richting Maasbrug. De ijzige oostenwind maakte de tocht niet makkelijk maar dreef het geluid van het gemekker richting Maas. Een van de grotere jongens droeg het bokje in zijn armen. Ze kwamen bij de plek waar ze de spoorbaan moesten oversteken. Met het hele repertoire aan standaardvloeken en emotionele uitbarstingen slaagden de mannen er in varkens en geiten tegen het schuine talud en over de naar de Maasbrug oplopende spoorrails heen te krijgen. De schildwacht bij de overweg had blijkbaar de luwte van wachtpost nr.49 opgezocht; vandaar dus geen reactie daarvandaan. Aan de andere kant van de spoordijk strompelde de karavaan tussen de struiken door naar het eind van de Moutstraat en bereikte eindelijk de kelder in de zandheuvel.

Levensonderhoud

De hele volgende dag had men nodig om zich in de ruime kelder te installeren voor vier gezinnen en twee onderduikers. Eten kon bereid worden in de woning van moutmeester R. verder op de Heijenseweg. Daar werd ook het meegesleepte vee gestald.

De grotere tieners moesten daarna dagelijks tijdens vuurpauzes de risicovolle weg naar bakker Jan Bernards in de Hei gaan. De drie tienerjongens kenden het heuvelachtig gebied achter de Heijenseweg als hun speelterrein in betere tijden. Verder in de week maakten ze kennis net de Duitse soldaten, die er bij hun gecamoufleerde geschutstelling lagen. De jongste soldaat was een jongen van 16 jaar. Die werd er regelmatig op uitgestuurd om in het ontruimde Gennep konijnen en kippen te vangen die daar los rondliepen. Want een militaire veldkeuken was er in Gennep niet. De hier gelegerde soldaten moesten maar in hun eigen voedsel voorzien.

Pipercup

De Luftwaffe bestond in dit frontgebied niet meer. Britse vliegtuigen waren hier heer en meester in de lucht. Elke dag hield een Pipercup de Duitse troepenbewegingen in de gaten. Bij Duits kanonvuur gaf de piloot de coördinaten door, zodat de Britten gericht konden terugvuren. De burgers moesten het toestel goed in de gaten houden, want elke bewegende gestalte was voor de piloot een vijand. Burgers waren in dit gebied immers geëvacueerd. De Duitsers probeerden de vijanden te misleiden door hun geschut steeds te verplaatsen. Signaleerde de Pipercup rook uit een schoorsteen, dan kon men daar binnen een paar minuten granaten verwachten.

Onder vuur

De tieners van de groep illegalen zouden geen tieners zijn als ze het gevaar niet miskenden. Ze liepen op hun manier voorzichtig richting Maas en wezen elkaar op de delen van de spoorbrug die schuin omlaag in het water hingen. Ze keken opgewonden naar de rupsvoertuigen die aan de overkant door de weilanden reden. Plotseling ratelden boordwapens en floten er kogels over hun hoofden. Ze waren ontdekt en voor soldaten aangezien. Ze hadden wel in de grond willen wegkruipen. Dit was hun eerste kennismaking met de Tommies en hier ook de laatste! Ze kwamen niet verder meer dan de struiken op de Logterbergen. |

%20Berk%202009%20(9).JPG)

Pipercup |

Wiel van Dinter, 5 feb 2020

Wiel van Dinter vertelt het nog onbekende verhaal van de Gennepenaren, die na de evacutie van oktober 1944n illegaal in Gennep achter bleven.

Na Market Garden